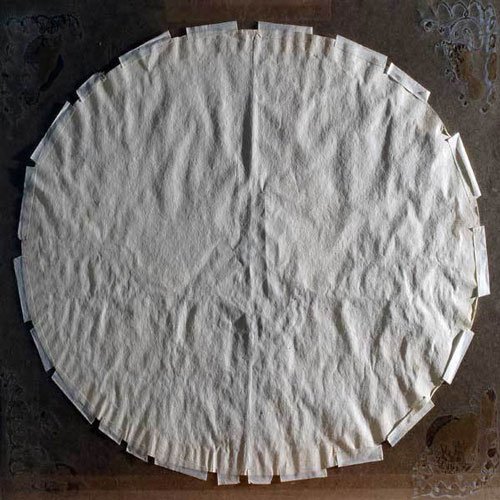

Above: Back of a paper illuminated with raking light; the hinging together with frequent changes In relative humidity have produce enough tension on the sheet to distort its planarity.

Below: An oil on canvas illuminated with raking light as well. The creases are the result of rolling the canvas with the painting towards the inside.

[/mp_text] [/mp_span_inner] [/mp_row_inner] [mp_row_inner] [mp_span_inner col="12"] [mp_image id="3188" size="full" link_type="custom_url" link="#" target="false" caption="false" align="left"] [/mp_span_inner] [/mp_row_inner] [mp_row_inner] [mp_span_inner col="12" style="min-height: 20px;" classes=" motopress-space"] [mp_space] [/mp_span_inner] [/mp_row_inner] [mp_row_inner] [mp_span_inner col="12"] [mp_image id="3186" size="full" link_type="custom_url" link="#" target="false" caption="false" align="left"] [/mp_span_inner] [/mp_row_inner] [mp_row_inner] [mp_span_inner col="12" style="min-height: 20px;" classes=" motopress-space"] [mp_space] [/mp_span_inner] [/mp_row_inner] [mp_row_inner] [mp_span_inner col="12"] [mp_text]Above: crack pattern formed on an oil on canvas, illuminated with transmitted light.

[/mp_text] [/mp_span_inner] [/mp_row_inner] [mp_row_inner] [mp_span_inner col="12" classes=" motopress-space"] [mp_space] [/mp_span_inner] [/mp_row_inner] [mp_row_inner] [mp_span_inner col="12"] [mp_image id="3512" size="full" link_type="custom_url" link="#" target="false" caption="false" align="left"] [/mp_span_inner] [/mp_row_inner] [/mp_span] [mp_span col="7"] [mp_row_inner] [mp_span_inner col="12"] [mp_text]In art conservation, when examining an artwork to outline a treatment proposal, conservators go through a process very similar to “close reading” a text. First, they look at the artwork, pointing out a couple of details, some damages, a peculiar type of brushstroke, the toothed chisel´s traces, … it is just a first encounter. Then they need to get into the key details: general understanding of the author’s technique, structure, materials, … Like in close reading, to do a treatment proposal, conservators go back to the artwork several times while taking notes and pictures, to extract the conclusions they need to embrace the treatment, whenever possible discussing the options with colleagues, sharing ideas, and interchanging opinions where the artwork is always the primary tool for forging the treatment proposal. It is an ongoing and recursive process to grasp a deep level of understanding of the piece and its circumstances, the alteration of the materials as well the depth and extent of the damages.

As it has been said, the artwork is the primary tool, but what other tools do the conservators use? From magnifiers to X-Rays, whatever tool can help them get a better understanding of the structure of the artwork and its overall condition.

One of the most frequently used tools is lighting. Playing around with the light can give a lot of information to conservators. For instance, raking light can very well highlight the topography of the surfaces and therefore is helpful in providing information about the soundness of the different strata in a painting or accentuate the presence of exfoliations in a stone. Transmitted light can help locating cracks and identifying their depth and extent. UV light can help determine the presence of over-paints, as well as the existence of residues from earlier treatments. An observation under sodium monochromatic light, makes all the tones of a painting become equal, only the yellows that remain the same, therefore, conservators can better study the structure of the painting with the naked eye. Contours and lines become sharper; some darkened areas under the varnish happen to be visible again, and on occasion, signatures or inscriptions can be identified.

Microscopes and/or macro photographs can help to discern between a varnish or a glaze, or assist to identify traces of an (in previous treatments) abraded signature.

Infrared photography makes sometimes possible to see through varnish and glazes, thus allowing the conservator to see a clearer image of the artwork, and again on occasion, discover hidden signatures or the initial drawing of the artist, as well as possible changes in the composition. X-Rays also provides information on the different layers of the artwork, as well as data like late additions, the presence of nails or rods, loose joints, or other structural issues. Both Infrared and X-rays are precious tools for the art historian since they can be an invaluable help to authenticate a work of art.

In brief, there are several tools available to conservators to get to know the artwork they are working with. The better the equipment the better the information obtained and therefore the better informed they are to properly outline a treatment proposal.

Above: With UV Light, Overpaints have a different fluorescence than the original paint and they appear as dark areas.

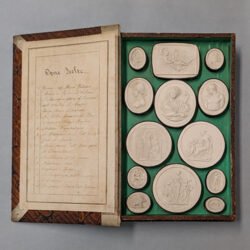

[/mp_text] [/mp_span_inner] [/mp_row_inner] [mp_row_inner] [mp_span_inner col="12"] [mp_text]Left: Fragment of an oil on panel: The ornamental painting was an overpaint. After taking a X-Ray image, we decided to remove it. The result talks by itself; a XV century painting was hidden under de overpaint.

1 - Wood panel with ornamental painting ; 2 - X-Ray ; 3 - Overpaint removal ; 4 - Final Result.

[/mp_text] [/mp_span_inner] [/mp_row_inner] [/mp_span] [/mp_row] [mp_row] [mp_span col="12" classes=" motopress-space"] [mp_space] [/mp_span] [/mp_row]